In Part I, I briefly covered how to use and zero weapon-mounted aiming lasers. Today I will discuss the tactics and techniques of night fighting, with and without lasers, in the face of an adversary who is similarly equipped.

Laser Discipline

Rule number one of wearing night vision is to not assume that you are invisible just because you’re wearing NVDs. Rule number two is to never assume that you are the only one with night vision.

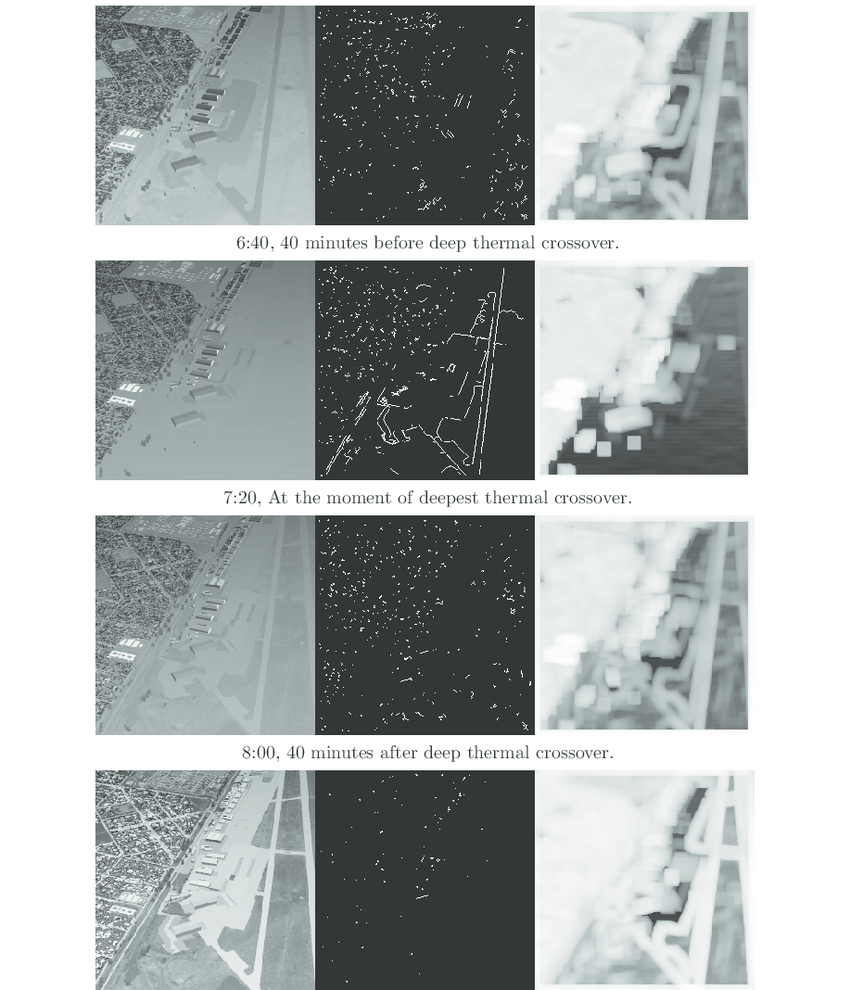

We use IR lasers for aiming because they are visible through night vision. Any night vision, not just yours. It’s a different world than it was 10-20 years ago, and what was revolutionary new technology is now commonplace. Even a $100 gen-1 night vision scope will see an IR laser. This does not mean that your laser is useless, just that you must adapt your tactics.

We can minimize the inherent vulnerability of lasers by exercising laser discipline. This means only turning on your laser for the bare minimum amount of time necessary to fire a shot and turning it off immediately afterwards.

weapon up – laser on – fire – laser off- weapon down

Notice that you do not turn on the laser until your rifle is up and pointed towards the target, and turned off before lowering the weapon. Failure to do this will trace a line on the ground from you to the target and back again, revealing your location.

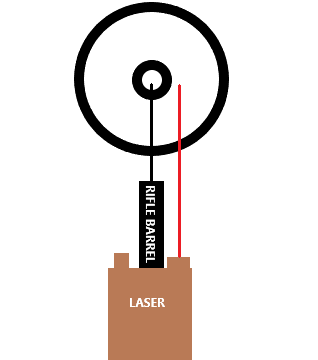

Laser discipline also means using your laser on low power for target engagement. For Class 1 civilian-legal lasers, this is not an issue since the laser is not capable of high power. However, if you have a full power (Class 3) PEQ-15, MAWL, or Perst-4, you should make sure your laser is on the lowest possible setting. This is because the high power setting will make the laser beam visible, where the low power setting only renders the aiming point “dot” visible. Observe the following examples;

This is not to say that there is no use for high-powered Class 3 lasers, just that you must be aware of the vulnerabilities inherent in their use. More on that in a bit.

Many laser units have an IR illuminator built in. This is essentially an IR flashlight that is paired with the laser to illuminate the target. I have personally never been in a situation where this was necessary, targets in dark rooms are plenty illuminated by the laser itself. Sure, you could use the illuminator to check dark areas, but that is bad practice in the face of a night vision equipped enemy.

Other Uses for Lasers

It is possible to use lasers to point things out to your teammates. However, this should be done very sparingly. Ideally, the only person to do this should be the team leader with a class 3 laser, and only in certain circumstances. A few examples of non-aiming uses for IR lasers are below:

- Designating sectors of fire at night

- Pointing out priority targets to automatic riflemen and anti-materiel rifle (AMR) gunners.

- Aiming skyward to indicate friendly positions (in dire circumstances only, this is a bad habit for non-emergency use).

- Locating lost personnel (laser skyward at regular intervals until found).

These are but a few. Again, I emphasize that this sort of use should be balanced against the threat of compromising the patrol. The team leader should use his best judgment to determine whether it is worth the risk to use an aiming laser for non-aiming purposes.

Night Fighting with Lasers

By this time you should understand that lasers should be used sparingly. You cannot turn on your laser and leave it on all the time, we call this “lightsabering”. This is how you get your whole team killed.

One piece of sage advice that rings true in any sort of combat is “never be predictable.” When it comes to night fighting, this means not getting too comfortable in any one firing position. Even with good laser discipline, eventually the enemy will zero in on your muzzle flash and laser point of origin. If you stay put, firing repeatedly from the same position, you will be targeted.

The solution is simple. Move. Move in between every shot if possible, or every two shots at most. Combined with laser discipline, your night fighting cycle should be as follows;

Get into position – weapon up – laser on – fire – laser off

laser on – fire – laser off – MOVE

I once was an OPFOR roleplayer for a military training exercise. I was acting as a guerrilla sniper in an urban environment, harassing a platoon of US Marines. I used my laser for every shot, and used the above night fighting cycle. Just to make sure the platoon knew they were being sniped (firing blanks), I even set my laser so that the beam was visible. In the AAR for that exercise, the trainees said that they saw my laser but it was never visible long enough for them to find its point of origin. I always moved buildings after firing two shots, and they could never pinpoint my location to return fire or send a maneuver element after me.

Bottom line, this method works. Practice this night-fighting cycle on your own to get the muscle memory down.

Passive Aiming

Passive aiming (without a laser) is often preferred to active aiming (with a laser) because there is no beam pointing out your position. This is made possible by three methods: night vision scopes, clip-on night vision devices, and helmet-mounted night vision paired with a red dot.

- Night vision scopes: Dedicated scopes for night engagement. These can vary in price from hundreds to thousands of dollars, with correlating variance in capability. These units normally do not allow daytime aiming without turning on the scope, so it’s best to use with a QD mount that holds zero (like AK side rail mounts).

- Clip-on NVDs: These mount on your rifle in front of your day optic and allow you to use your day optic at night. Bear in mind that some clip-on NVDs will introduce parallax, and have a slightly different point of aim. If you use one of these, be sure to check your dope when using them. Then record it. Know your equipment.

- Wearable night vision + red dot: This technique is perhaps the most cost-effective, but requires a night vision compatible dot to avoid damaging your NVD. A very effective setup I’ve seen repeatedly in class has been an LPVO/prism optic with a small dot mounted on top. This places the dot high enough to be easily viewed through helmet-mounted NVDs.

None of these techniques changes the night fighting cycle I listed above. You are still giving off muzzle flash, and you still need to move to avoid being targeted.

Other Night Fighting Considerations

Your muzzle flash is the number one thing that an enemy shooter will zero in on. You should take measures to mitigate it with a good flash hider or suppressor. Muzzle brakes have no place on fighting rifles, they enhance the flash so that you are both easier to target and temporarily blinded after each shot. Muzzle flash can also be hidden from the enemy through techniques such as loophole shooting and firing from deep inside of rooms.

Weapon-mounted flashlights have limited utility. If using a laser compromises your position, shining a visible flashlight is MUCH worse. Mind, I’m not talking about home defense or concealed carry, I’m talking about light infantry style combat. In this context, the only acceptable use for a visible weapon light is clearing structures, and even then, caution must be exercised. In Iraq, US forces clearing structures with white lights often took fire from other buildings because the enemy saw the lights through windows and knew that Americans were there.

White lights should not be mounted to weapons during rural patrolling. The risk of someone accidentally triggering their light on patrol is too great to risk it. Once you get tired you start to get lazy and stop paying attention to how you hold your weapon and accidentally hit the pressure switch. I don’t care how many safeties are on your light, the risk is still present and the consequences too high. My white light has a quick-detach mount so I can store it in my butt pack, mounting it to my carbine only when necessary.

Summary

This article covered a lot. We learned that laser discipline is critical and that movement is key to our survival. We discussed passive aiming techniques and the basics of night fighting. Finally, we discussed some general tips for night fighting.

At this point you may be wondering which is better, laser or passive aiming? I say that although passive aiming is superior, you should have both capabilities. There are just some things that a laser can do that passive aiming cannot, like get reliable hits from awkward shooting positions (i.e. prone, twisting around inside vehicles, etc.) and inflict a frustrating psychological effect on your enemy. I personally run both capabilities, with a red dot mounted above my 3x prism and a Perst-4 on the front of my rifle.

Whatever you choose, make sure you practice with it. Whether it be a laser, passive aiming, or even a weapon light, practice the night fighting cycle I mentioned above. Movement is key to making yourself harder to target. If you cannot be targeted, you cannot be hit.

Practice makes perfect, and training enables good practice. I’ll be adding more classes to the spring 2023 training schedule in the next few weeks, including the long-awaited Jäger Course. Stay tuned! Email me to sign up for a class.